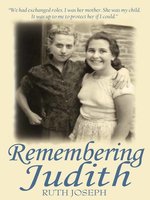

From the cover

Your bloody memory taps you on the shoulder when your back is turned. Smell that perfume. Remember when your mother used to wear it?

I am small. About four years old. A scene many of you who were children in the 50s will remember. She's off to a party. She's promised she'll show me her dress. I lie in my bed waiting, it seems, for hours. Then she pushes open my door and wakes up the dark with a rustle of taffeta, a swish of silk and a mist of perfume.

'Let's see, Mummy – let's see! Please, put the light on.'

She laughs a tinkling sound, not her usual laugh, but in her special other-people voice. She moves to the switch and, suddenly, the room is neon-bright. I blink, rub my eyes, unaccustomed to its dazzle, and she is standing there like a film star, blonde hair set in rigid Marcel waves curling into her slim face, her narrow pale shoulders exposed above folds of shot fabric. Her skirt is decorated with appliqué leaves and flowers, and she twirls on six-inch crocodile platform shoes. She is beautiful. But the vision lasts only seconds. The warmth, the laughter, is gone with a 'Sweetheart, you must go to sleep now'. She leans over the bed planting a dark-red kiss and laughs when it marks my cheek, rubbing the smear with a red-nailed finger. Then she is gone and I am back in the black, and the dressing gown returns to the face of a witch, the man in the moon laughs through the curtained window, and the monsters under the bed sharpen their claws to catch me if I dare dangle a foot.

But later, much later, I hear shouts from their bedroom. They are arguing and I can hear her sobbing – it begins as muffled whimpers and intermittent cries like the yelping of a lost puppy. But she often cried – that's what girls do, isn't it? The sound becomes louder, and now he is screaming indistinguishable words at her. I call and call. Nobody comes. The monsters are flexing their talons and won't let me get out of bed. So I sing to try to drown their scratching and the bad from that room, with a high-pitched lisping of a repertoire repeated from Music While You Work. Then I'm Wilfred Pickles, muttering in a broad north-country accent to 'Give 'em the money Mabel'. Eventually, I fall asleep.

In the morning, I sit with our mother's help in the breakfast room. She's made me some porridge. I never like it when she makes it. It is decorated with black bitter flecks. It lies crouching in a blue and white striped dish like a grey solid mound surrounded by a moat of luke-warm milk and topped with a scab of brown sugar crust. I'm excavating broken lumps swimming round the bowl, trying to force the stuff down, concentrating on Housewives Choice, which is playing 'Spanish Eyes' and selections from the 'Desert Song' to busy ladies at home in Sidcup and Chichester. My mother walks into the room. She is cross because our help has dressed me in my second best Shabbat outfit – a navy knitted skirt and jumper decorated with bunches of red knitted cherries and bleach-white socks. I know she'll make me change into last year's clothes, now designated as playing clothes. So we make our way back up the stairs, me begging to leave off the liberty bodice. But I'm aware that it's hopeless and first the liberty bodice and then the old tight clothes are forced over unwilling limbs. We come downstairs and I'm duly inspected.

'That's better,' she says. 'Good enough for playing in.'

I looked at her bright smiling face, eyes swollen from hours of crying – the colour masked with Pancake. I want to ask about the crying and the shouting, but somehow, even at four, I know not to. The rules are set. Tidy. Neat like my...